A piece of history – a comprehensive documentation of the World Cup 1965 in Sweden with lots of detail and background information. In the gallery at the end of this article you will find numerous previously unpublished photos of this event from private photo albums.

The fourth international contest for radio controlled aerobatic aircraft was held at Ljungbyhed in Sweden from September 9th to 15th.

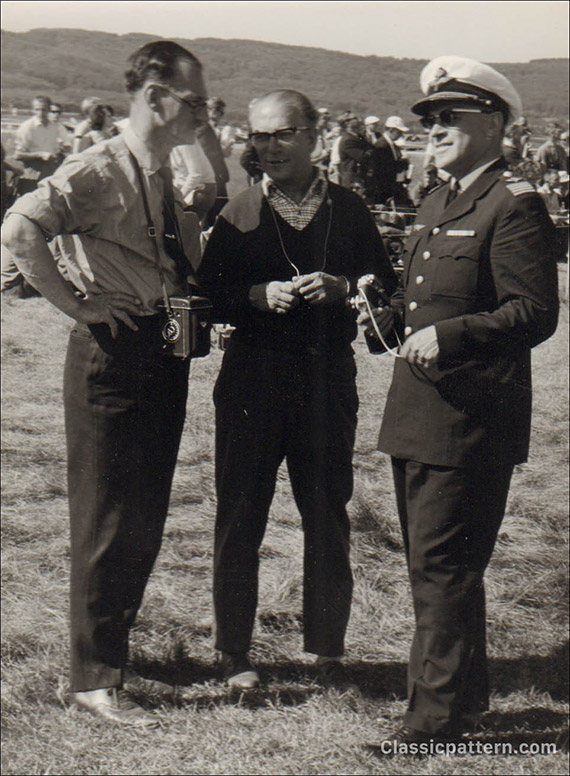

There were several modifications to the system of running the World Championships this year, for example; six judges were used; Stewart Uwins from Great Britain, Norbert Trumfheller, Sigurd Heiret, Gordon Gabbert from U.S.A., Louis Leroy, Juergen Schwabe.

Provided by UK Classic Aerobatic Association.

Thanks to our british friend Martyn Kinder.

Powered by www.classicpattern.com

Carl XVI. Gustaf of Sweden

The flying order was fixed so that each contestant flew at approximately the same time each day, luckily, the weather conditions were fairly consistent, although the early morning fliers may have had a slight advantage over those flying later in the after-noon when a breeze sprang up each day. This is our only unfavourable comment on the whole meeting, which was extremely well organized.

The new World Champion Ralph Brooke with his wife and winning plane Crusader

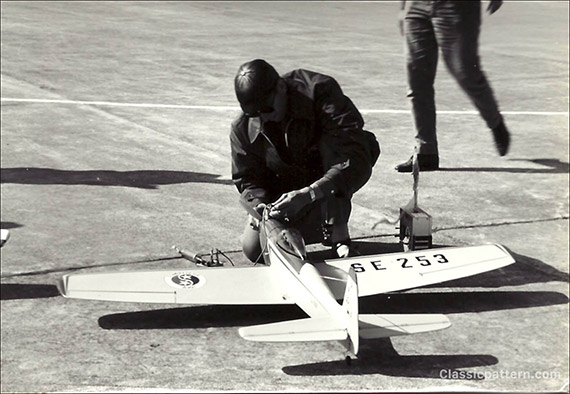

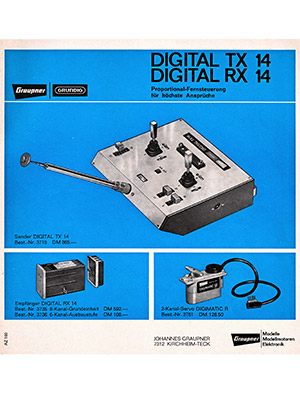

Most models were equipped with proportional gear and digital systems were much to the fore. There were in fact 10 Bonner Digimites and one Multiplex, two Simprop, two C.R.C. Proportional, two Orbit Digital, two Orbit Analog, two Constellation, seven Digital, two home made proportionals, one Kraft proportional, one Sampey Starlight proportional, and 10 assorted reed outfits one of which was home made. Orbit had two new Digital control outfits on show, flown by Ralph Brooke and Zell Ritchie.

The British contingent, Chris Olsen had F & M with Soraco amplified Duramites, Stuart Foster was using Orbit 10 with Transmites and Peter Waters had Min-X with Annco servos.

There were several of the new German Simprop outfits among the German team although Fritz Bosch was the only one in the team to use it for the contest. The Constellation 7 was a local product used by the South African team the third member using Kraft Proportional.

Kato brothers Japan

Proportional brought with it a great deal of low flying making it a little difficult for the judges, we thought. However, as these gentle-men were spaced out for different view points, the collective result to their score proved to be quite consistent. It is interesting to note that the only ‘prangs’ occurred during practice and fun sessions between rounds.

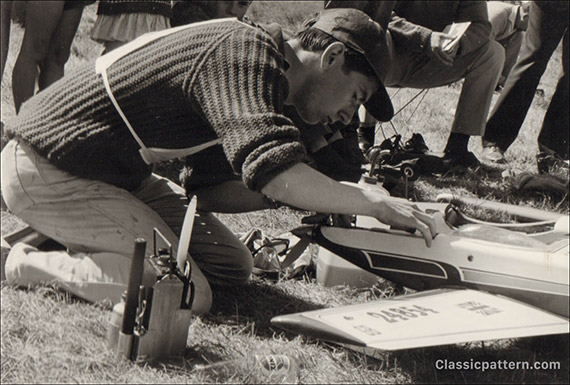

The vice world champion 1963 Fritz Bosch with his Delphin

There were some near misses however, when Blauhorn’s model went fail-safe (it was not executing straight and level on either of these occasions). Fritz Bosch was flying Simprop in his “Delphin” this was the third reserve model, his first pranged in practice, the second reserve was a biplane which although it flew very nicely was obviously less acceptable to Fritz for the actual competition flight.

Fritz Bosch with biplane Wik Tiger

Stephensen of Norway had an interesting piloting technique with Digimite transmitter tucked under his chin, he really showed how proportional throttle could be used to control each section of each manoeuvre. The effect must have impressed the judges for his marks showed well as he had adequate time to position the model precisely for each manoeuvre on very low throttle.

The flights were made fairly late in the afternoon after the sea breeze had died down. Readers may remember his earlier gallant efforts with home-built and later in Belgium with modified Dee Bee Proportional. Ralph Brooke, flying early in the day seemed full of confidence as usual although was a little less jubilant after the first flight.

The winner Ralph Brooke

Chris Teuwen from Belgium made a considerable leap forward, using a model which had only a week or so previously been considerably repaired. The score showed an improvement on Brooke’s first round flight, sailing way ahead of him in the second round. Cliff Weirick flying a `Candy’ with glass fibre fuselage also continued to improve throughout three flights (it should be noted that all three flights counted in this competition).

Chris Teuwen Belgium, the new Vice World Champion

Chris Olsen put in a good first flight which he bettered a little in the second and improved considerably in the third round. The top five places remained more or less constant throughout the meeting Stephensen displacing Olsen on the last day.

Stewart Foster put in a creditable performance although was marked somewhat lower than Olsen. Our third string Peter Waters had a rather disappointing first flight but strode ahead again in the second two.

It is interesting to note that the three British reed fliers showed very little difference in performance with the proportional outfits. Chris Olsen for example executed most of his straight inverted pattern `hands off’; the sure test of a correctly trimmed model.

The three British models were; a new design by Olsen known as “Upset”, low winged slightly tapered with the appearance of having been developed from his earlier “Uplift”.

Jiri Michalovic, Czecho-Slovakia

Foster was using his “Nimbus II” and Peter Waters number six of a series of “Altairs”. One of the outstanding models of the competition was R. E. Chapman’s (Canada) “Norseman 4” resplendent in gold finish with De Bolt retract gear on all three wheels. It looked really beautiful when inverted, although he had a little difficulty in starting and twice had to go to the end of the round when the motor failed to fire with the model cradled inverted in its stand on the take-off spot.

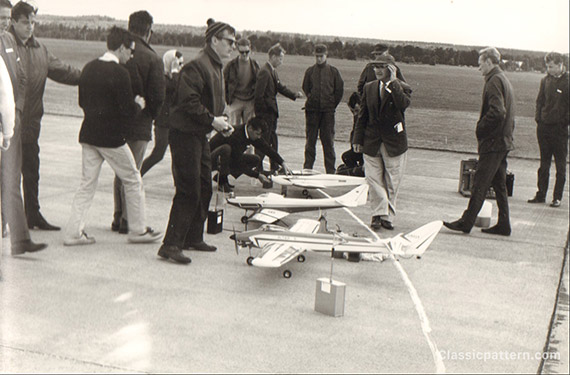

In the front the beautiful plane “Welshman” Pilot Wanter / England

While on the subject of engines we really must comment on the gallant effort of J. Michalovic of Czechoslovakia who with extremely limited resources at his disposal in that country built his own engine, 9 c.c. complete with R/C throttle. The motor slogged gallantly away although it blew a head gasket in the second round and failed to throttle back on the third. Nevertheless all modellers at the meeting, it seemed, were pushing those control sticks for him mentally… . A stout effort!

Now for a few notes on the general standard of flying. Even if it were not a World Championship event, we would liked to have seen some of the competitors place their manoeuvres more consistently. Clearly some were flying as if there was no wind at all, the occasional breeze did upset the flight pattern for these models and loops noticeably skewed as a result.

There is a certain technique in performing before judges and it seemed that perhaps in the heat of the contest some of the competitors either forgot their bearings in relation to the judges or plainly were not used to slightly varying weather conditions. Some of the low flying was too low to judge whether it was straight although it showed that it certainly was level. Really large loops seemed difficult to judge so there was hardly any point in flying enormous loops which occasionally turned out to be egg-shaped. The contrast from the fairly tight loop of the reed flier was obvious, perhaps when proportional has settled itself with the modellers they will gradually reduce the amount of use they make of the facility for large, wide manoeuvres.

Ronny Chapman`s “Norseman”

As the contest drew to a close it was obvious that if there was to be a battle between Chris Teuwen of Belgium and Ralph Brooke of U.S.A., for first place Teuwen would have to produce a continuation of his score increase, which he failed to do falling short by some 50 per cent of the expected percentage in-crease. Ralph Brooke however soared ahead with 7,188 points. Chris Olsen would also have to do even greater things to produce a score to beat Stephensen on the same basis. However, Stephensen made an even larger increase in his score as will be seen from the results table below.

Fritz Bosch`s Wik Tiger

If the meeting lacked the excitement of a fly-off, it certainly made up for it in crowd appeal by the free-lance demonstrations put on by four Draken deltas of the Swedish Air Force and by American, German, Dutch and British modellers who flew a collection of unorthodox manoeuvres. The Germans in particular executing very tight dual performances with several near misses. This went on until the flying developed into a “Limbo” contest with models flying low inverted from all directions. The obvious and expected result was that some decided to go below ground level and the most spectacular being a Dutch device which having ground its piano wire whip aerial away in a magnificent shower of sparks lost all radio contact and finally melted its cockpit canopy on the runway. Pete Waters then decided to go one better and stay at about 4 ft. altitude for almost a quarter of a mile until the Brass got just too Jong for him. . . .

Well, it does one good to let off steam after the trials of a World Championship.

Thanks are due to the magnificent co-ordination of the organization of the Swedish Aero Club and particularly to Ralph Dilon, who besides being rushed hither and thither to assist in the organization, also flew in the contest, harassed as he was. He has connections with “Tetrapack”; a packaging firm who sponsored the meeting. Ljungbyhed really looked after competitors and supporters alike with com-fortable billets and lashings of food and hospitality. . . .

We vote this one of the best R/C World Championship meetings so far.

| Place | Pilot | Country | Weight kg | Plane | Engine | Engine |

| 1 | Brooke, R. | USA | 3,15 | Crusader | Merco 61 | Orbit Digital |

| 2 | Teuwen, C. | Belgium | 3,17 | Trouble | Tigre 56 | Bonner Digimite |

| 3 | Weirick, C. | USA | 3,95 | Candy | Veco 61 | Bonner Digimite |

| 4 | Stephansen, P. | Norway | 3,1 | Maximum-4 | Merco 61 | Bonner Digimite |

| 5 | Olsen, C. | England | 3,2 | Upset | Merco 61 | F&M 10 Reed |

| 6 | Pitchie, Z. | USA | 3,75 | Phantom IV | Fox 59 | Orbit Digital |

| 7 | Chapman, H. | Canada | 3,35 | Norseman 4 | Merco 61 | CRC Electronics Proportional |

| 8 | Foster, S. | England | 3,35 | Nimbus II | Merco 61 | Orbit 10 Reed |

| 9 | Blauhorn, K. | Germany | 2,87 | Taurus | OS-60 | Multiplex-Proportional |

| 10 | Tom, H. | Canada | 3,0 | Cutlass | Tigre 60 | Kraft Proportional |

| 11 | von Segebaden, J. | Sweden | 3,8 | Mustfire | Merco 61 | Bonner Digimite |

| 12 | Bosch, F. | Germany | 3,65 | Delphin | Tigre 56 | Simprop-Proportional |

| 13 | Sweatman, C. | South Africa | 3,55 | Decoder | Merco 61 | Constellation 7 Proportional |

| 14 | Hitchcox, W. | Canada | 3,35 | Norseman 4 | Merco 61 | CRC Electronics Proportional |

| 15 | Haegeman, G. | Begium | 3,08 | Zinneken | Tigre 56 | Bonner Digimite |

| 16 | Rasmussen, H. | Danmark | 3,6 | Beach Comber | Tigre 56 | Bonner Digimite |

| 17 | Waters, I. | England | 3,1 | Altair-6 | Merco 61 | Min-X 12 Reed |

| 18 | Corghi, E. | Italy | 2,3 | X-18 | Tigre 51 | Controlair 10 Reed |

| 19 | Kato, S. | Japan | 2,96 | Thunderbird | Tigre 60 | Orbit Proportional |

| 20 | Wessels, J. | South Africa | 2,9 | Taurus-Mod | Veco 45 | Bonner Digimite |

| 21 | Mantelli, 0. | Italy | 2,75 | Taurus | Veco 45 | Bonner Digimite |

| 22 | Gugliolminetti, F. | Italy | 3,0 | KK Original | K&B 45 | Bonner Digimite |

| 23 | Hakche, J. | Danmark | 3,2 | Beach Comber | Merco 49 | Homemade 10 Reeds |

| 24 | Bauerheim, K. | Germany | 3,5 | Corsar | Tigre 56 | Homemade-Proportional |

| 25 | Culverwell, C. | South Africa | 2,77 | Taurus-Mod | Veco 45 | Constellation 7 Proportional |

| 26 | Levenstam, J. | Sweden | 3,7 | Mustfire | Merco 61 | Kraft 10 Reed |

| 27 | van der Burg, A. | Holland | 3,57 | Hazwena | Merco 61 | Orbit 10 Reed |

| 28 | van Vliet, P. | Holland | 2,95 | Blizzard | Merco 61 | F&M Prop |

| 29 | Kato, M. | Japan | 2,92 | Thunderbird | Tigre 60 | Orbit Prop |

| 30 | Tonnesen, U. | Norway | 2,9 | Flint Stone | Merco 61 | Homemade Propoflex |

| 31 | Dilot, R. | Sweden | 3,0 | Taurus-Mod | Merco 61 | Min-X 10 1 |

| 32 | Dedobbeleer | Begium | 3,24 | Demoiselle | Tigre 56 | Bonner Digimite |

| 33 | Andersen, E. | Danmark | 3,75 | Original | Merco 61 | Bonner Digimite |

| 34 | Martens, F. | Holland | 3,27 | Humple | Tigre 60 | Orbit 12 Reed |

| 35 | Michalovic J. | CSSR | 3,4 | Original | Home made 9cc | Orbit 10 Reed |

RCM&e 10/1965

Images: Collection Streil / Urs Leodolter